This blog post is inspired by the British Library exhibition – Listen: 140 Years of Recorded Sound. It is not exactly about the exhibition but some thoughts on preservations of obsolete audio formats.

Those who followed the HBO TV series, Westworld (2016), must have impressions of the recurrent player-piano with punched paper roll, sampled some of Radiohead’s cathartic tunes. It is a riveting idea to juxtapose a legacy mechanical digital format and modern digitally recorded music. Whereas in actual timeline, it took more than 100 years to go from the invention of a self-playing piano to the first commercial release of digital music compact disc in 1982[1]. In the heyday of Music CDs, cassette tapes became obsolete, and vinyl disc fell out of fashion. During the early days of CD manufacturing, PCM tape was a major storage media for studio to record the master copies. It was later replaced by DAT (Digital Audio Tape), launched in 1987.

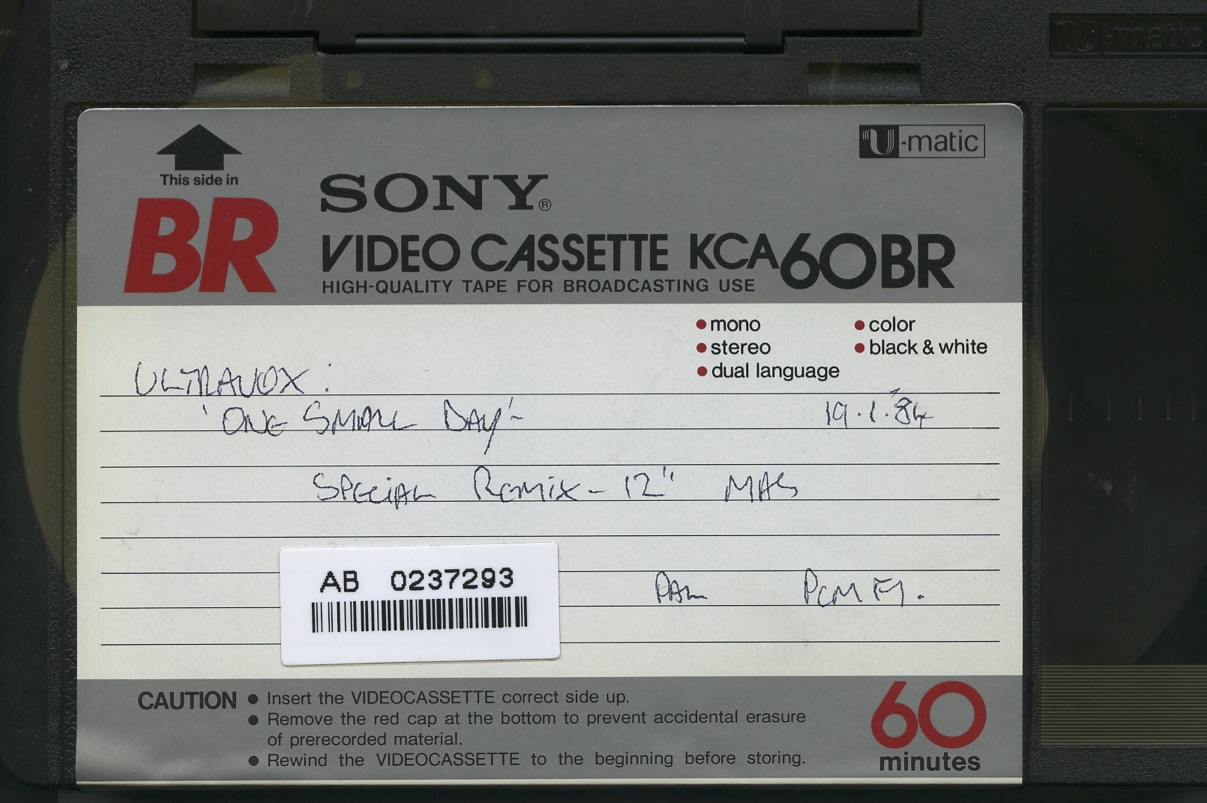

Talking to a record company guy who manages a sizable 80s and 90s catalogues, following a buyout from one of the majors, he revealed that they had tens of thousands of Sony PCM 1630 U-Matic and DAT storing in their archive, among other formats like ½”, ¼” Ampex open reels. A big portion of these tapes were masters for CD production. Now, they are all in need of some tender loving care despite storing in a costly and controlled environment. Of which, U-matic PCM tapes were described as urgently in need to be digitally re-formatted or transferred. Not to mention the challenge of transcribing the idiosyncratic metadata written on the package. Obviously, this is not something restricted to an independent record company, but an extensive scale of risk on losing large amount of information recorded on these early digital formats.

U-Matic tape was developed as an analogue recording videocassette format, introduced in 1971, with a vision to match the commercial success of Philips’ audio cassette system[2]. Instead of gaining popularity in the mass market, it became widely adopted by broadcast industry. By late 1970s, Sony developed a special PCM (Pulse Code Modulation) adaptor—the PCM-1[3]. Until late 1990s, many CDs were mastered on U-Matic PCM-1610 or later PCM-1630 cassettes. According to an advert in Billboard issue 3 Nov 1979, PCM-1600 has the following properties[4]:

DROP-OUTS HAVE BEEN DROPPED – Sony engineers have created an ultra sophisticated digital connecting code that can actually restore ‘drop out’ information.

DIRECT TO DISC QUALITY WITHOUT DIRECT-TO-DISC LIMITATIONS – Because digital quality doesn’t deteriorate from one tape generation to another, the PCM-1600 let you make generation after generation of lacquers[5]…

The problem started from how perpetual it appeared. These statements have ironically become an omen to a lot of record companies and sound archives. “Digital quality doesn’t deteriorate” sounds metaphysical enough but the storing media certainly degrades. Just like other magnetic tape based cassettes or open reels, they have sticky shed syndromes [6], especially when they are stored improperly. According to a Billboard article[7] published in 1999, since these music information is stored digitally, they cannot be spliced and repaired like analogue open reels, nor could they leave their housing and baked to dry out. The writer of the article overtly switched on a ringing siren to warn about the calamity. 18 years on, we know that a portion these recordings have been digitally ‘remastered’ and dropouts are ‘digitally spliced’. Indeed, it takes a monster to deal with a monster. Avid music fans take triumph to spot these ‘clicks’ and ‘pops’ (aka audiophiles)[8] resulted by splicing, and blog about them. Whereas the truth persists, a track which has been digitally remastered IS NOT the original. If the original master is not playable or available any more, future reissues might need to remaster from a remaster. This is not dissimilar to photocopy a photocopy – more and more depth and details are lost along the way.

Apart from material deterioration, another big concern is the increasingly unavailability of hardware and parts for these machines are no longer manufactured. Maybe the solution is that old equipment must be archived along with its data as suggested by Robinson & Bowden[9].

Do record companies see these magnetic tapes merely as non-current asset? Or would they see themselves as custodian for some containers of modernity? I was told that a possible future of those early tapes formats would be destroyed following all data transferred and back up in suitable format(s) (But what is a suitable format?). This may save a hefty sum of storage fee, as well as the salary of an archivist, plus possibly a (false) sense of reassurance. However, when it comes to preservation and curation, Floridi reminded us that the key lies in brain-power, not computer power[10] to decide what to preserve, how to preserve and how much to preserve. These curation decisions owe a lot to the fact that there is limited resources, for both the public or commercial sector. PCM U-matic is only one of the antiquated formats among many others that need to be dealt with. We know that this is an expensive affair. Most business (and institutions) have no or very little budget assigned to support preservation[11]. In 2008, a commercial broadcasting group donated the whole pre-90s archive to British Library for better preservation expertise and to free up a room in the office block.

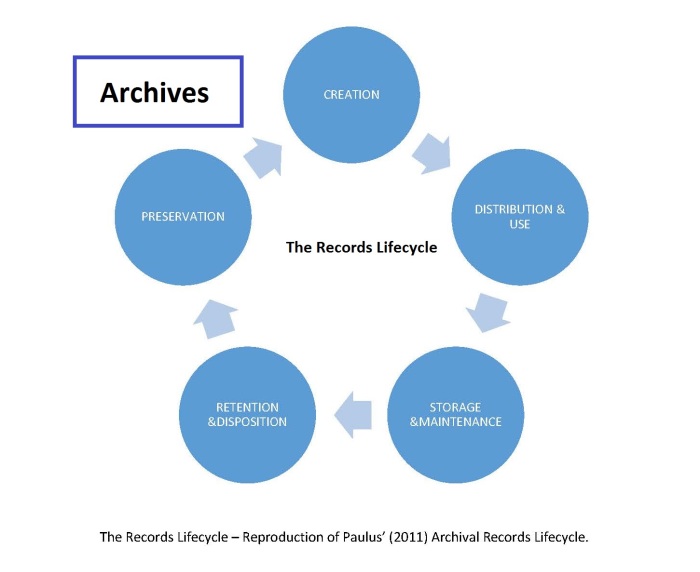

Michael J. Paulus’[12] discussion on preservation in relations to his model of Archival Cycle, is also relevant to a commercial music archive, albeit it was derived from academic libraries and archives. Fail to preserve signifies breakage of the lifecycle.

Physical storage media need to be preserved, to maintain the integrity of the bits that reside on them, and the logical ordering of the bits needs to be preserved, to make them “renderable” or readable in the future. There is also the bigger and more basic question of responsibility: who will save what, when, how, and where? Common computer applications and uses do not do much to support long-term access, therefore digital materials are at risk if they are not proactively curated.

Maybe we should always resort to the grooves on a humble vinyl.

Notes and References:

[1]Compact Disc Hits 25th birthday. [News Article] (17th Aug 2007). BBC News.. Retrieved 1st Nov 2017.

[2] Martin, J. (2007) 3/4” U-matic Videotape [Curriculum Module]. Retrieved 25th October, 2017.

[3]Sony Home Audio History [Web Page]

[4]Sony Digital Audio [Magazine Advertisement] (3rd Nov 1979) Billboard – the International Music –Record –Tape Newsweekly Music, Video and Home Entertainment, P. 46-47.

[5] During vinyl production, grooves are firstly cut onto a lacquer disc. After that a metal stamper used for production is created from the lacquer.

[6] Fox B. (8 Dec 1990) Technology: Record industry faces up to sticky tape problem. New Scientist. Retrieved 26th Oct 2017.

[7] Holland, B. (17th Jul 1999). Digital archives face deterioration: As with analog tapes, DAT and U-matic masters breaking down. Billboard – the International Newsweekly of Music, Video and Home Entertainment, 111, 1-1, 105. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.uwl.ac.uk/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/981598?accountid=14769

[8] Here is an example of how an influential audiophile community had criticised the remastering errors of a new David Bowie box set, released in September 2017. http://www.superdeluxeedition.com/news/parlophone-respond-to-david-bowie-berlin-box-set-mastering-criticisms/

[9] Bawden D. and Robinson L. (2012) Introduction to information science. London: Facet

[10] Floridi, L. (2014) The 4th revolution : how the infosphere is reshaping human reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[11]Richard Wright, (2004) “Digital preservation of audio, video and film”, VINE, Vol. 34 Issue: 2, pp.71-76, https://0-doi-org.wam.city.ac.uk/10.1108/03055720410550869

[12] Paulus, M. J. (2011) Reconceptualizing Academic Libraries and Archives in the Digital Age. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, Volume 11, Number 4, October 2011, pp. 939-952 (Article)